Art Hostage has been a thorn in the side of all concerned relating to the infamous Gardner art heist for decades.

Art Hostage has been toxic in his views about the criminals, law enforcement and the Yellow Journalists who have written about the Gardner art heist for the main(slime)stream media and followed the bullshit line spewed out repeatedly over the last 25 years.

Now, for the first time, Art Hostage can offer the solution that finally recovers the Gardner art.

First of all the Gardner Museum must make a new reward offer by way of a public statement of intent, highlighting the actual conditions needed to claim the reward.

Something along the lines of:

"The Gardner Museum of Boston declares after 25 years of searching without success a new detailed reward offer.

This reward offer is based upon a 1% percentage of the Market/retail value (or the total reward being up to $5 million for all the Gardner artworks, whichever is the largest amount given the possible damage to the Gardner artworks over the years since) stolen of each stolen Gardner artwork recovered upon its recovery and any damage to the condition since it was stolen in 1990.

This reward will be paid in full for each Gardner artwork returned and not require the total Gardner artworks stolen back in 1990 to be recovered.

For example, if the Vermeer is recovered, it will be inspected and valued, then a reward of 1% percent of it current value, in its current condition will be paid out forthwith with no other conditions to apply.

This will apply to all stolen Gardner artworks as and when they are recovered.

A simple test can be applied by offering information about a lesser value Gardner artwork, for example a drawing by Degas, to test the validity of this renewed 2015 publicly offered reward"

The actual legal language can be arranged to suit the legal process but the main focus is to offer a collectible reward, taking into account the possible damage or less than Good condition the Gardner art may be in after 25 years. By doing this it will send a clear message to those who can give the vital information as to the whereabouts of the elusive Gardner art and reassure them the reward is real, sincere and legally binding, as well as the reward will be paid out on each individual stolen Gardner artwork, as and when recovered.

This solution is practicable, honest, sincere and will go along way to reassure the scepticism of those within the close knit circle that know the whereabouts of the Gardner art.

Secondly, the so-called immunity from prosecution offer being touted all these years is a false offer as explained by The then Assistant Boston D.A. Brian Kelly, back in 2010 at the IFAR meeting in New York. The then Assistant Boston D.A. Brian Kelly explained that anyone stepping forward to claim immunity would have to provide details of what they know and give up their right to take the fifth amendment as well as agree to testify against those responsible for holding the Gardner art. That is why the offer of immunity has not been challenged by the media and the endless line of Yellow Journalists who have all followed the spin of falsehoods for the last 25 years.

Law Enforcement and the D.A. office in Boston must, alongside the new reward offer made by the Gardner Museum, issue a press release giving details of the immunity offer which will rest assure those who can help, they will not have to provide any information other than their location of the Gardner art and will not face any prosecution for any Gardner art heist related possible crimes.

The wording would be something along the lines of this:

"We, the office of the District Attorney in Boston declare that anyone offering the location of the Gardner art will not face any indictments, charges or be required to give any details of how they came into the knowledge of the Gardner art whereabouts whatsoever.

The Soul Intention of the Office of the District Attorney in Boston is to see the Gardner art recovered and not to prosecute anyone who provides the location of the Gardner art

Furthermore, we declare the reward offer made by the Gardner Museum 2015 to be lawful and do not object to the Gardner Museum paying the reward out to anyone who offers the location of the Gardner art on the 1% percentage basis of the Market/retail value (or a total of $5 million for all the Gardner artworks whichever is the greatest amount given the possible damage to the Gardner artworks since their theft) of the condition which the said Gardner art works are in upon recovery, as well as the reward being paid out for each Gardner artwork as and when they are recovered"

Again, the wording can arranged to fit the legal requirements but the jist and message is clear that the immunity offer is a full immunity for the Gardner Art Heist exclusively.

Whilst this may not sit well with all it would demonstrate the sincerity of all concerned as they have been declaring for many years the recovery of the Gardner art is paramount, not prosecuting anyone.

It is amazing, or perhaps not, that for all the many many column inches devoted to the Gardner art heist, not one journalist has asked any questions about the reward offer or immunity offer. They just spew out the same old tired bullshit year after year hoping to catch a break and hoodwink the public.

Furthermore, those with knowledge of the Gardner art whereabouts are not law abiding people and therefore they know there needs to be a concrete reward offer and immunity offer before they step up.

We have never been dealing with law abiding citizens. so why assume they would have any moral fibre and guilt to hand back the Gardner art?

With these new 2015 reward and immunity offers in place then the likes of Jeanine Guarente, Elene Guarente and Earle Berghman (Bobby Guarente's best friend) as well as Robert Gentile would be more willing to offer up what they know about the current whereabouts of the Gardner art.

For the sake of clarity, yet again, I Art Hostage, want to declare publicly that I seek not one dime of any reward, do not seek any payment at all.

Furthermore, if I can assist in any way, shape or form to help anyone with knowledge give the location of the Gardner art, again I seek not one dime of any reward, and in fact would not seek any credit for my assistance and would allow others whom want the spotlight to step forward to claim they helped.

My sole purpose has always been the return of the Gardner art to its rightful place for the enjoyment of the public and if I can assist in that process all well and good and I would be prepared to step back and allow others, who's egos consume themselves, to claim the undeserved credit.

I would say however, if I assist in any way, shape or form to recover the Gardner art I would sincerely hope that recovery would be dedicated to the memory of the late, great Harold Smith

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DXer/Ross gives two links which are well worth consideration:

http://www.boston.com/news/2015/03/18/the-many-dead-ends-the-gardner-heist-investigation/7lJrNHTmLJP8bX0Qxst8gK/story.html

This is facinating:

http://photos.syracuse.com/yourphotos/2013/03/isabella_gardner_art_heist.html

Isabella Gardner art heist

Below, former Maine residence and barn of Robert Guarente searched by FBI in 2009

The Many Dead Ends of the Gardner Heist Investigation

Two thieves, 13 stolen masterpieces, and a 25-year search for justice.

The Boston Globe

Twenty-five years ago, in the early

morning hours of March 18, bartenders kicked tipsy St. Paddy’s day

revelers out onto the streets and locked the doors of their pubs. Around

the same time, two men dressed as police officers walked up to the the

side door of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Eighty-one minutes

later, they left with $500 million worth of stolen art. It remains the

biggest art heist in history, and no one has ever been charged with the

crime.

The bizarre robbery and murky details

surrounding it touched off a 25-year chase filled with false starts,

close calls, and dead ends. But, as the empty frames await the return of their missing art, FBI officials say they’re determined to solve the case that has baffled them for decades.

“This artwork belongs not only to the

Gardner museum, but to the city of Boston and the art world as a whole,”

FBI special agent Geoff Kelly, the bureau’s lead investigator on the

case, told Boston.com. “To be able to recover these pieces and return

them to the museum would finally close the last chapter of one of the

most enduring and perplexing mysteries the FBI has ever worked.”

Here’s a look back at the twisted tale of the Gardner heist:

THE THEFT

March 18, 1990 1:24 a.m.:

FBI

Richard Abath, the security guard on

duty, sat in a tight office, occasionally looking up at four monitors.

The doorbell rang. Abath said two men in police uniforms told him they

needed to come inside to investigate a disturbance. Abath buzzed them

in. According to the Gardner museum’s website, he “broke protocol” by doing this. Abath would later tell The Boston Globe that he didn’t know the museum’s policy against letting in uninvited guests applied to police officers.

Abath told NPR recently

that the thieves had him call his partner back. The thieves then took

both men to the basement, where they covered the guards’ eyes and mouths

with duct tape and handcuffed them to a pipe and a workbench.

Boston Police Department

At this point, the thieves had the run of the museum. According to The Globe,

there was only one button in the entire museum to activate the alarm,

and it was at the guard’s desk. There was also a system of motion

sensors throughout the building that could track their movements, which

the thieves (unsuccessfully) tried to disarm, allowing investigators to

trace (most of) their steps after the fact.

The thieves moved slowly and deliberately. As The Globe

said at the time, “the thieves appeared to have set their sights on

specific works, having left behind many of equal or greater value.”

WHAT THEY STOLE

Motion sensors indicated the thieves first entered the

second-floor Dutch Room, where they took six paintings. They dropped

the frame of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn’s painting on the floor, and

smashed the glass covering the canvases of Johannes Vermeer’s “The

Concert” and Govaert Flinck’s “Landscape with an Obelisk.” The Rembrandt

hung on a secret door that looked like a wall panel. Investigators

found the door open, which they said indicated the thieves had inside

knowledge.

FBI

The sensors showed that one of the

thieves went into the Short Gallery, which is also on the second floor.

He took the Degas sketches, as well as a flag finial.

FBI

The Blue Room, on the ground floor near

the museum’s public entrance, may have been the thieves’ last stop,

though it’s impossible to know for sure; the Blue Room’s sensors never

detected anyone in that room after a guard’s rounds at 12:53 a.m. But,

at some point, the thieves took a Édouard Manet oil, “Chez Tortoni,”

removing the security bolts that fastened it to the wall.

FBI

2:41 a.m.:

The first thief left the building through

the side entrance. Four minutes later, the second thief exited. With

them were 13 out of the 2,500 pieces housed in the museum. The art

varied in scope and size, and was initially valued at $200 million. That

figure was updated to $500 million by 2005.

None of the artwork was insured.

7:30 a.m.:

Abath and the other guard remained bound

and gagged in the basement for several hours. Abath later told NPR that

he stayed calm during this time by singing Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released”

to himself. When a maintenance worker and a daytime guard arrived for

their shifts and no one was there to buzz them in, they knew something

was wrong.

“As they stood there, puzzled, a security supervisor arrived with keys. He opened the door; no guards were in sight.‘My guards are missing!’ he told [Lyle] Grindle, the museum’s security director, in a phone conversation made shortly after walking in the door. ‘We’ve been robbed . . . and it’s very serious.’‘Have you called the police?’ asked Grindle.‘Yes.’‘Secure the building; I’m on my way,’ Grindle replied. He was so frantic to get to the museum that he cannot remember which car he drove.The call to 911, on a quiet Sunday morning, crackled over the police radio. Boston police Detective Sgt. Paul Crossen had just exited from the Southeast Expressway when he heard it. Crossen immediately spun his steering wheel and headed toward the Fenway. The phone call bearing news of the theft jangled in Anne Hawley’s kitchen, catching her in midconversation. Edward M. Quinn, the supervisory special agent of the FBI’s Reactive Squad, was sitting in church when his beeper summoned him to the scene of the heist.” (The Boston Globe, May 13, 1990).

They’ve been working on the case ever since.

The Boston Globe Archives

THE INVESTIGATION

Just after the robbery, the museum offered

a $1 million reward for the returned artwork. The investigation

initially focused on the guards and three unknown individuals whom, The Globe reported, tried to create an early-morning “disturbance” outside the museum two weeks prior to the robbery.

Security officials were quick to comment on the lack of training the museum guards had.

“There is not enough pay, not enough

training, not enough maturity,” Steve Keller, a national consultant on

museum security, told The Globe, adding that Gardner

administrators “didn’t cut corners on equipment. They didn’t buy the

cheap brand. The equipment didn’t fail. Someone made a human error and

let someone in.”

“You know, most of the guards were either

older or they were college students,” Abath told NPR. “Nobody there was

capable of dealing with actual criminals.”

“They tell you exactly what to do if someone is damaging a painting,” a guard told The Globe a few days after the heist. “You put your hands up in the air and blow your whistle.”

Tom Landers/The Boston Globe

But it was soon revealed that the museum

itself wasn’t equipped to deal with criminals, either. The only burglar

alarm in the entire museum, inside and out, was a “panic button” by the

front desk, which was effectively useless as soon as the guards left the

area. And none of the artwork was insured.

About two weeks after the robbery, the museum formed a security panel. The Globe published an article further illuminating the many problems the museum had before the heist:

“The truth was, though, that the museum had been in trouble long before the robbery. The Gardner had simply failed to keep up with standard late-20th-century museum practices. There wasn’t even an adequate place for visitors to hang their coats, let alone a climate-control system to protect the museum’s masterpieces from the extremes of Boston’s winters and summers. The problem was a matter of money and management. The trustees, traditionally a self-perpetuating Brahmin board of seven Harvard-educated men, acted as if fund-raising were tantamount to begging. In the 1980s, when there was big money available for arts institutions, the museum didn’t even apply for big grant money—at a time when the Gardner needed millions of dollars’ worth of climate control and conservation.” (The Boston Globe, April 22, 1990).

Two months after the robbery, the police

had received around 1,000 tips. They made no arrests, but pinpointed

about a dozen suspects around the globe. According to The Globe,

investigators had two theories: Either the paintings were stolen to

collect on a ransom from the museum, or they were taken on the behalf of

a collector.

THE FIRST SUSPECT

One name that surfaced early in the

investigation was Myles Connor, a notorious New England art thief who

was first charged with art theft in 1966 and spent the next several

decades in and out of jail for similar crimes. He told the Patriot Ledger

in 2013 that

he had planned a heist of the Gardner museum in 1988, but never

followed through. Connor was in jail at the time of the 1990 heist.

AP

1991

On the first anniversary of the theft, The Globe reported

that the museum raised $700,000 to install a climate-control system.

The security system was also upgraded, though officials would not say

how.

Museum membership, meanwhile, was up 50 percent.

1992

On the second anniversary of the heist, Terry Lenzner, a private attorney hired by the museum to work on the case, ran ads in The Globe and other national newspapers encouraging people with any information to call a toll-free hotline.

At this point, the ransom theory was mostly discounted because so much time had elapsed. Lenzer told The Globe in March that he believed they were stolen for a black market collector.

“We’re not going around to pawn shops,” Lenzner said. “Other than that, we’re not excluding any possibilities.”

“There just isn’t any hard information surfacing,” Lenzer added. Though The Globe

reported that the museum and the FBI spoke to each other about the case

weekly, Lenzer said “it’s safe to say that we’re not about to announce

that we’ve found the objects.”

“We’re not going around to pawn shops.”

In June, The New York Times

wrote that as many as 40 FBI agents were working on the case at a

time, and that they had “at least one intriguing subject”: Brian

McDevitt, a 31-year-old screenwriter from Swampscott who had already

served time for an attempt to rob the Hyde Collection in Glen Falls, New

York, in 1980. Authorities said his plan in that heist was similar to

what was ultimately occurred at the Gardner, though he was caught before

he could carry it out.

McDevitt denied any involvement, and his

lawyer said it was impossible for him to have been involved because he

had an alibi and a beard, while both suspects in the Gardner heist had

only moustaches.

60 Minutes interviewed

McDevitt about the Gardner heist in a November 1992 episode. He

continued to deny any having any information about the robbery.

1993

Even so, McDevitt was called to testify before a federal grand jury in August about his whereabouts at 1 a.m. on March 18.

“McDevitt’s lawyer, Thomas E. Beatrice, told WCVB-TV (Ch. 5) yesterday that he’s been assured by prosecutors that his client is not a target of the probe and was subpoenaed ‘presumably to provide some testimony or evidence in their investigation.’ But, Beatrice said his client knows ‘absolutely nothing’ about the Gardner heist. ‘We don’t think he can provide anything that could aid them in this investigation,’ he said.” (The Boston Globe, August 7, 1993)

McDevitt died in 2004. He was 43.

1994

The investigation was given new life in

April, when the Gardner museum received an anonymous letter offering to

help return the art for a $2.6 million ransom and full immunity from

prosecution for those involved. The author asked for the museum to

respond by printing a code in May 1 edition of The Globe: the number 1 in the US-foreign dollars exchange listing for the Italian Lira. The Globe obliged in what it called a “community-service decision”:

The Boston Globe

The Globe

said that after the secret code was printed, the museum received a

second letter from the source, who seemed encouraged by the Gardner’s

willingness to negotiate, but alarmed by what he called an aggressive

reaction from law enforcement. He wrote: “Right now I need time to both

think and start the process to insure confidentiality of the exchange.”

He never wrote again.

A POSSIBLE SIGHTING

1997

On the seventh anniversary of the heist, the museum’s

board of trustees increased the reward offer from $1 million to $5

million.

The Globe reported

that a few months later, in August, William P. Youngworth III, facing a

variety of charges including receiving a stolen van, illegal possession

of ammunition, illegal possession of three antique firearms, illegal

possession of marijuana, and being a habitual criminal, told the FBI he

could provide information about the heist in exchange for having his

felony charges dropped.

Youngworth provided what he said were details about the heist to the Boston

Herald:

“The thieves who posed as police officers and forced their way into the Gardner museum in the Fenway had on an earlier visit left an unalarmed museum window unlocked so they could use it as an alternative entrance; that they damaged several bolts that were used to secure the paintings to the wall, and that one of the thieves pulled out a pocket knife and cut two of the Rembrandts from the frames because of the difficulty of removing the bolts. Sources familiar with the investigation said it was public knowledge that the paintings were slashed. Beyond that, they said that so far Youngworth has not offered any convincing details about the heist.”

Connor, the man who was first charged with

art theft in 1966 and was in jail at the time of the Gardner heist,

re-entered the picture when Youngworth demanded his release from jail

(and the $5 million reward) as additional conditions for his assistance.

According to the Los Angeles Times

, Youngworth did so because Connor was his “oldest and dearest friend.”

A few weeks later, authorities brought

Connor to Boston to testify about his involvement. Youngworth also

appeared on an episode of Nightline where he claimed to be able to deliver the art.

Tom Landers/The Boston Globe

In late August, Herald writer Tom Mashberg told a strange story. An associate of Youngworth drove him to a warehouse (which was either an hour outside Boston or in Brooklyn,

depending on which of Mashberg’s accounts you read) to view what

Youngworth claimed was the stolen Rembrandt painting “The Storm on the

Sea of Galilee.” Mashberg said the canvas was unrolled from a tube and

illuminated by a flashlight in the dark warehouse. Mashberg was later

given paint chips that were supposed to have come from the stolen work,

as well as photographs of other pieces. The Herald hired an expert to analyze the chips, who concluded that they came from a Rembrandt.

Though Mashberg’s glance was fleeting, The Globe

reported that “a key investigator said that the FBI and US attorney’s

office, lacking a significant break in the spectacular case, had no

choice but to assume the painting is authentic.”

Mashberg said the canvas was unrolled from a tube and illuminated by a flashlight in the dark warehouse.

On September 23, The Globe reported

that Connor said David Houghton, a former mechanic and associate who

died in 1992, was the mastermind behind the heist. But, The Globe said,

those who knew Connor suspected he was trying to pin the crime on

someone who was already dead in order to secure his own release from

jail.

Youngworth was convicted of possessing a stolen van in early October and returned to prison.

Meanwhile, the Herald turned the paint chips over to the Gardner museum for analysis. In the December, the results were in. Contrary to what the Herald’s expert found, the museum said the chips were not from a Rembrandt.

And so ended the negotiations with Connor and Youngworth.

1999

Former FBI agent Larry Potts, now working

for the Gardner, wrote to Youngworth pleading for his cooperation and

help returning the stolen art. Youngworth refused to meet with Potts,

but he wasn’t completely opposed to negotiating:

“ ‘Yes, I would be delighted to help you and the Gardner Museum recover their former property,’ Youngworth wrote on June 21. ‘Kindly remit $50 million dollars U.S. and a signed immunity agreement issued by the Attorney General of the United States.’” (The Boston Globe July 1, 1999).

EVEN MORE NAMES

2000

Three new names emerged in the investigation. The Globe reported

Carmello Merlino and David Turner, who were charged with plotting to

rob an armored car company that year, had been questioned about the

Gardner heist in February 1999. The FBI also questioned their associate,

former Boston police officer Peter Boylan, The Globe said.

2004

Youngworth’s name came up yet again when, in an interview with ABC’s Primetime Thursday about

the case, he said reputed Charlestown gangster Joseph P. Murray, who

was shot to death by his wife in 1992, told authorities in the early

1990s that he could provide information about “a major art theft” in

exchange for the release of an unnamed IRA prisoner jailed in England.

“I’m not saying who he reached out to, but

Joe Murray had the ability to end this thing where everyone winds up

happy, but they wouldn’t pick up on him,” Youngworth said. (The Boston Globe May 11, 2004).

2007

An unnamed “former employee” of the museum told The Globe

that a federal grand jury would hear evidence that three people, not

two, carried out the crime. The employee said that authorities told him

they “were hoping that the grand jury would ‘shake things up’ in the

long-stalled investigation.” It didn’t.

2009

Around the 20th anniversary, many

journalists wrote books about the heist. One of them was Ulrich Boser,

who released “The Gardner Heist.” He named Turner as the most likely

suspect.

Not to be left out, The Globe also reported on potential evidence against Turner:

“While in Miami, three days before the Gardner robbery, Turner purchased $645 worth of unspecified merchandise from the Spy Shops International in Miami, a store that specialized in the sale of undercover and electronic surveillance equipment. Also viewed by the Globe was a receipt that showed Turner’s American Express card was used in Fort Lauderdale on the return of a leased car on March 20, 1990, two days after the robbery. While the receipt appears to be signed by Turner, another person’s Social Security card number is written on the receipt, which investigators say suggests someone other than Turner might have been using his credit card that day. Goldstein, Turner’s lawyer, declined comment on the documents.In addition, Turner was observed by police surveillance in September 1991 carrying an ‘Oriental vase’ from his car into the Boston office of Alfred Sollitto, a lawyer with whom he had become acquainted. Among the 13 items stolen from the Gardner Museum was a vase-like, Chinese bronze beaker. Sollitto acknowledged in an interview that he was a friend of Turner’s but could not recall Turner ever bringing a vase to his office.” (The Boston Globe, March 15, 2009).

2010

Hoping advances in forensic technology over the last 20 years would reveal something new, the FBI resubmitted evidence from the crime scene for further DNA testing.

“ ‘If they left any sweat on that duct tape, a sample could be drawn, and with that sample there’s the possibility of a result,’ said Dr. Bruce Budowle, former senior scientist of the FBI’s Quantico lab.The FBI conducted DNA tests on items taken from the crime scene at the time of the theft, but none of the tests produced a usable sample.Huge strides in DNA analysis in the two decades since the crime could mean a different outcome this time.”

Amazon

Another book about the case was released, this one written by retired FBI agent Robert K. Wittman. In Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World’s Stolen Treasures,

Wittman said that in 2006 and 2007, he posed as a wealthy art collector

interested in purchasing several of the paintings through two Frenchmen

who had ties to Corsican mobsters. The Frenchmen claimed they could get

him the Vermeer and at least one Rembrandt, but investigation fell

apart because, Wittman said, of bureaucratic infighting between federal

agents and supervisors.

An article in Boston Common magazine about the 20th anniversary of the heist also implicated Turner:

“The evidence against Turner is

significant, and FBI files describe how Turner’s crime boss, Carmello

Merlino, tried to offer information about the paintings in exchange for a

reduced prison sentence shortly after being picked up for a drug charge

in 1992. The last witness to see the thieves before they entered the

museum described one of the thieves as having ‘Asian eyes,’ and Turner

fits that description.”

2011

Mashberg wrote a book about art theft with

Gardner’s chief of security, Anthony M. Amore, but Amore didn’t mention

the Gardner heist because, Mashberg would later say, the “hunt had reached a delicate phase.”

FERRETING OUT THE ART

2012

The Globe

reported that the widow of Robert Guarente, a friend of Merlino’s, told

authorities that she saw her husband give Robert Gentile a painting in

2003. The FBI believed Gentile had ties to the Boston faction of

Philadelphia’s Mafia.

In May, authorities searched Gentile’s Connecticut home using everything from a radar to a ferret. Nothing was found.

Jessica Hill/AP

Gentile denied any role in the heist. But his lawyer, Ryan McGuigan, told The Globe in November that he “knew some of the individuals that the government believes may have had something to do with the heist.”

2013

On March 18, 2013 — the 23rd anniversary of the Gardner Museum theft — the FBI announced that it knew

the names of the thieves but would not disclose them. They also said

that some of the works had been put on the black market in Philadelphia

in the previous decade.

Steven Senne / AP

In May, Gentile was sentenced to 30 months

in prison for unrelated charges. Although he denied any involvement in

the Gardner theft.

“Prosecutors said for the first time in open court Thursday that their continued interest in Gentile in relation to the Gardner was based in part on a list they found in his home of the 13 works of art that were stolen in the heist, their estimated value, and a Boston Herald article published days after the theft. They also said a polygraph test he took about his knowledge of the heist concluded with a 99 percent assurance rate that he was lying.” (The Boston Globe, May 10, 2013).

Matthew Cavanaugh/The Boston Globe

Investigators also returned to Abath, the security guard. In his first public interview about the heist, he told The Globe

in 2013 that he met with FBI agents to discuss the case in 2009 and

was questioned by federal prosecutors in 2012, where “investigators all

but accused him of stealing the missing Manet.”

Abath denied any role in the theft.

“I totally get it. I understand how suspicious it all is,” Abath told The Globe.

“But I don’t understand why [investigators] think . . . I should know

an alternative theory as to what happened or why it did happen.”

2014

FBI Special Agent Geoff Kelly, the bureau’s lead investigator on the Gardner Case, said the FBI

had confirmed sightings of the works. He also named Carmello Merlino,

Robert Guarente, and Robert Gentile as the main persons of interest.

WHERE WE STAND NOW

Kelly told Boston.com that, 25 years later, the agency remains hopeful the crime will be solved.

“These paintings are hundreds of years old

and 25 years is a relatively short period of time,” Kelly said. “Stolen

artwork typically is returned either soon after the theft, or

generations later.”

The investigation remains active and ongoing. The frames are still empty.

5 Theories About the Greatest Unsolved Art Heist Ever

On March 18, 1990,

two police officers—or so they seemed—walked into a Boston museum and

left with $500 million worth of paintings. They have never been found.

The two thieves seem to have gained access to the Isabella Stewart

Gardner museum in the wee hours of the 18th by claiming they were

investigating a report of a disturbance (remember, they were dressed as

cops). They then detained the guards and proceeded to cut priceless

paintings out of their actual frames, making off with thirteen works

including paintings by Degas, Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Manet. These

paintings have never been recovered—despite the $5 million reward.

The heist has fascinated and obsessed people for exactly 25 years. It's

become a career-defining investigation for more than one journalist,

several of whom have written entire books and even become entangled with

law enforcement themselves in their quest to uncover the paintings.

Yesterday, one of these journalists—Tom Mashberg, author of Stealing Rembrandts—recounted his years on the hunt for the works in The New York Times, where he frequently covers art theft and repatriation. He also mentioned a litany of other theories, which themselves are completely fascinating. Let's take a look.

Boston Mobsters Did It

The prevailing theory—the one that the FBI thinks is correct—is that

the heist was the work of local mobsters. This is the most likely

explanation, and it odds are good that even if other theories turn out

to be true, this version of events played a role. The Boston Globe explains:

[The FBI] points to a local band of petty thieves — many now dead — with ties to dysfunctional Mafia families in New England and Philadelphia. It also suggests they had help from an employee or someone connected to the museum.

The FBI said as much in 2013,

saying that the Bureau had a "high degree of confidence" that the

stolen paintings eventually made their way south towards Philly and even

Connecticut, where they were sold. "With that same confidence, we have

identified the thieves who are members of a criminal organization with a

base in the mid-Atlantic states and New England," the FBI said during a press conference.

But even if

these figures were involved, which seems pretty likely at this point,

there are a number of places the paintings could have wound up—and a

number of ways they could have gotten there.

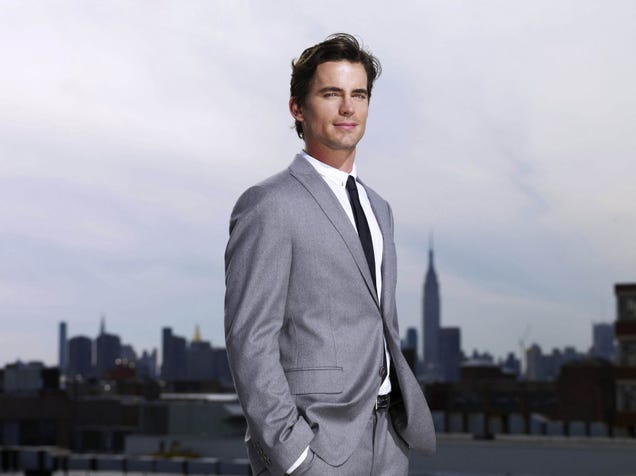

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Special Agent in Charge Richard DesLauriers in 2013. AP Photo/Steven Senne.

The Irish Republican Army Did It

The "Irish connection" is an auxiliary theory—it suggests that the

thefts were carried out in Boston by local criminals in order to help

the IRA. Perhaps local criminals sent the paintings to the IRA to help

finance operations across the Atlantic? Here's how author and Boston

Globe journalist Kevin Cullen put it in 2013 in an interview with WBGH:

"I never ruled out the idea the IRA was involved," he said. "Because, if you go back to that period particularly, the IRA was actively stealing art in Europe. They were stealing art from some of the big mansion houses in Ireland and then fencing it somewhere in Europe. So I never completely ruled that out, but it sounds like the authorities have ruled that out."

This is one

of several theories that involve European criminals and dealers—after

all, these paintings were all painted by middle European artists, with

the exception of a Chinese vase that was also stolen.

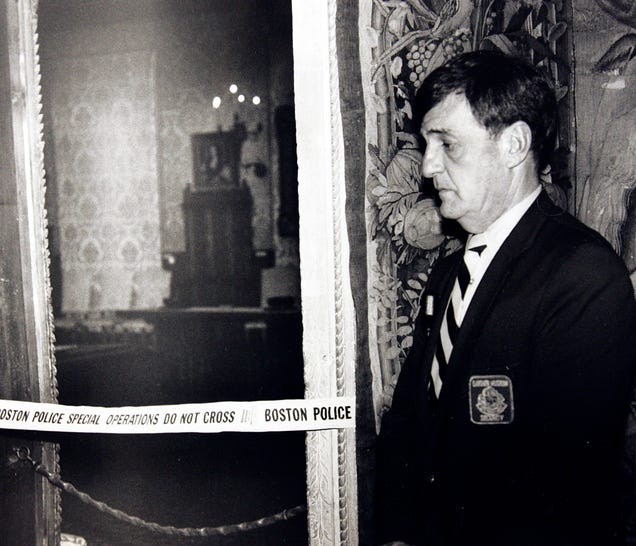

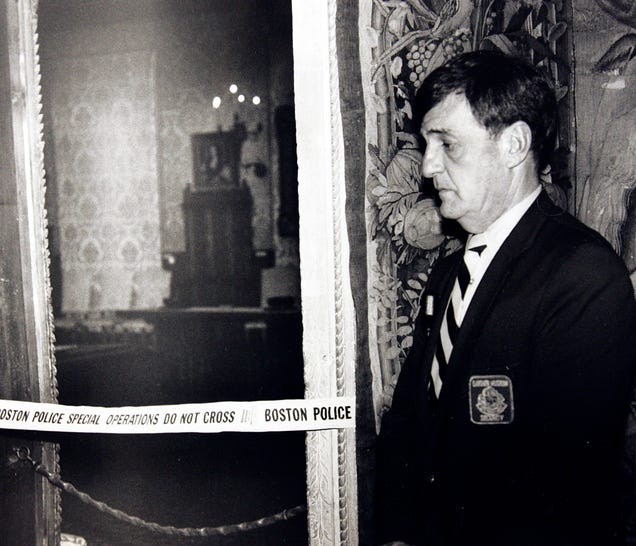

A security guard stands outside the Dutch Room of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990. AP.

A Famed Art Thief Orchestrated It

In the

beginning, specific figures were fingered as possible suspects. For

example, there was Myles Conner, a well-known art thief, who became an

early suspect in the crime—even though he was in jail. Ulrich Boser,

author of The Gardner Heist, described Connor in 2010 on PBS:

He was a Mayflower descendant, he was a member of Mensa, he headed a band called Myles Conner and the Wild Ones that played with Roy Orbison and the Beach Boys, and he was a prolific art thief. He had stolen Japanese statutes; had stolen Colonial-era grandfather clocks; stolen old master paintings; he robbed the Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.; he robbed the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

But Connor would have had to design the heist via prison, if he was really involved. A few years ago, Mashberg himself commented on WBUR

that it's entirely possible Connor played a role in the heist, since he

was peripherally involved with specific mob figures the FBI says played

a part in the crime.

The French-Corsican Mob Did It

So, about

those Europeans. The founder of the FBI's Art Crime Team, Robert K.

Wittman, believed he was near recovering at least some of the works when

he conducted an undercover operation targeting French-Corsican

criminals who claimed to be selling works by Rembrandt and Vermeer. In his 2011 book, Priceless – How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World's Stolen Treasures, Wittman describes how in the end, the French police blew his cover and the operation was ruined. Read more about it here.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Special Agent Geoff Kelly in 2013. AP Photo/Steven Senne.

The Paintings Were Destroyed After the Thieves Panicked

But what if the crime wasn't as dramatic as all that? What if it was

the equivalent of a joyride—a dumb and badly planned robbery by

criminals who didn't fully understand what they were doing? And when they realized just what they had done, they trashed the loot? The author of The Art Forger, Molly Parr, described a personal theory along these lines in Jewish Boston:

My theory is that someone then did it as a lark, just to see if they could do it. And once they did it, they kind of asked, now what? They couldn't sell them, so they decided to dump the paintings at the dock. But the truth is, no one knows! Anything is possible. It's a 25-year-old ongoing crime.

But the NYT yesterday, Mashberg talked to the FBI agent on the case, Geoff Kelly, who has serious doubts about that idea:

Mr. Kelly said he rejected the notion that the art was destroyed by the thieves as soon as they realized they had "unwittingly committed the crime of the century." "That rarely happens in art thefts," Mr. Kelly continued. "Most criminals are savvy enough to know such valuable paintings are their ace in the hole."

In the end,

this is a fascinating story for reasons beyond the crime itself. The

work of brilliant journalists like Mashberg have played a pivotal role

in the FBI's investigation. In a way, the Gardner heist set a precedent

for the many independent journalists who are investigating cold cases

today. Of course, it's also a cautionary tale about public

participation—the hundreds of leads that the FBI has followed have all

gone cold.

Will the

paintings ever be rediscovered? The grimmest fear seems to be that the

paintings were hidden by the criminals—and the criminals are now dead.

As the decades pass, the odds of finding the paintings could be slipping

away, too. Let's hope that's not the case, and that the quarter century

of work by journalists and investigators won't come to nothing.

So, what do you think? Do you have your own theory?

Lead image: The empty frame from which thieves cut

Rembrandt's "Storm on the Sea of Galilee," seen here in 2010. AP

Photo/Josh Reynolds.